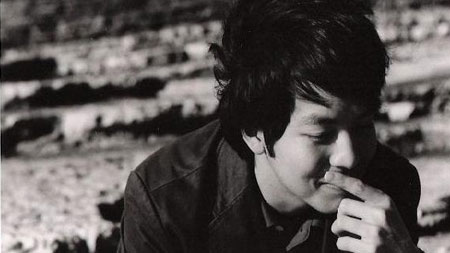

Dept of Congratulations: Kiik Araki-Kawaguchi

We are very pleased to announce that Kiik Araki-Kawaguchi’s story “dissolving newspaper, fermented leaves” received a “Special Mention” in the Pushcart Prize XLI Anthology.

For a sneak peek, read the excerpt below, then purchase a subscription to Pleiades here.

Kiik Araki-Kawaguchi

dissolving newspaper, fermenting leaves

To persuade her cricket to eat, Margaret Morri cooked every recipe she’d learned when she’d cooked for her family in Venice. As the rest of the Morri family barrack slept, Margaret slipped into the camp’s mess hall and raided its pantry. She minced pork, garlic, ginger, green onion. She arranged dumplings in a pan and ladled hot oil over them until the dough of their skins became tan and chewy. She boiled fistfuls of buckwheat noodles, plunged them into ice baths, and spun the strands into shallow bowls. She caramelized sweet onions and doused meatballs of beef tongue in rice wine and vinegar. She uncloaked the pits of umeboshi plums and rolled the sweet, puckered flesh into sheets of salted and dried seaweed.

She held them out to her cricket and begged him to eat. But he just stared at her dishes impassively, stroked the ends of his antennae, and turned his face away. On the mornings Margaret was not attentive to the aesthetics of her offering, her cricket wiggled his mandibles in disgust, and emitted a sharp, pompous click from the toothcomb tucked beneath his wings.

At the camp library there was a single book containing a passage about the lives of crickets. That book was World of Insects: Grasshoppers and Katydids, and if Gila River’s resident entomologist had cared to check its record, they would have discovered it had been signed out by an M. Morri a total of twenty-eight times. Based upon her research, Margaret assembled woodcrates of dissolving newspaper, fermenting leaves, ripe pods of fungi, and delivered them to the burrow of her cricket. Her cricket approached a decomposing leaf, sniffed at it, bristled, and leapt away. From her oldest uncle, Margaret learned that it was common practice for crickets to cannibalize the wounded. So she tore the hind legs from a desert locust and presented them to her cricket, who recoiled, let loose a series of heated chirps, and would not appear to her for several days.

Though her arms were branded by flares of hot grease and steam, though her olfactory nerves grew tired and raw, though her eyes clouded from lack of sleep, Margaret continued to dribble hot oil onto chicken skin until it curled into a sail of sweetened fat. Margaret steamed custards of tofu, ponzu, green onion and whipped eggs in teacups. Her hands clapped pots of white rice into steaming wedges and garnished their peaks with tart strips of shoga. And if her rice balls were finished before the sun had risen, she transferred them over to an open fire, toasted them, lowered them into a ceramic bowl, and splashed over them a broth made from kombu and flakes of bonito dashi.

– You must eat, she said.

But her cricket merely balked his wings, pronounced a fierce, staccato snort.

– If you will not eat what I cook, then what will you eat? she asked.

– Her cricket said, there is just one thing I can eat.

– I will make you anything, Margaret pleaded.

– When you lie down to sleep tonight, her cricket said, place me beside your left ear. We will find each other in your dreams, and I will be able to eat there.

That night, when Margaret went down upon her bedroll, she did as her cricket had instructed. She placed her cricket in a little nest of hair beside her left ear and was quickly overtaken by the blackness of sleep.

During the first months inside the fences of the Gila Relocation Center, Margaret’s dreams would transport her back to her family’s home in Venice, California. But in the past two years, all Margaret’s dreams had been pulled as though by a tether back to Gila. On this occasion, when she came into awareness, she found herself sitting in the darkness of the barracks, and her cricket had assumed the form of a man. She knew this man was her cricket because he was humming a song and cleaning his teeth with a wooden splinter. Her cricket was slightly reminiscent of the Reverend Jun Ishimoto, the minister from the Venice Methodist Church. He was lean and immaculate, hair and fingers well-manicured, and something of his smile seemed slightly misaligned, as though his mouth was over-crowded with teeth….

To read the rest of the story, subscribe to Pleiades.